MEDEA (2022)

- Duration ca. 55'

-

Libretto

Stephanie Fleischmann

Click here to read

Instrumentation

soprano, 6-part vocal ensemble, and sixteen players

Click here to read

Instrumentation

soprano, 6-part vocal ensemble, and sixteen players

- Commission Commissioned by Ensemble Musikfabrik and Kunststiftung NRW

-

Premiere Date

June 3, 2023

Sarah Maria Sun, soprano

Schola Heidelberg

Ensemble Musikfabrik

Cologne, Germany

More Information

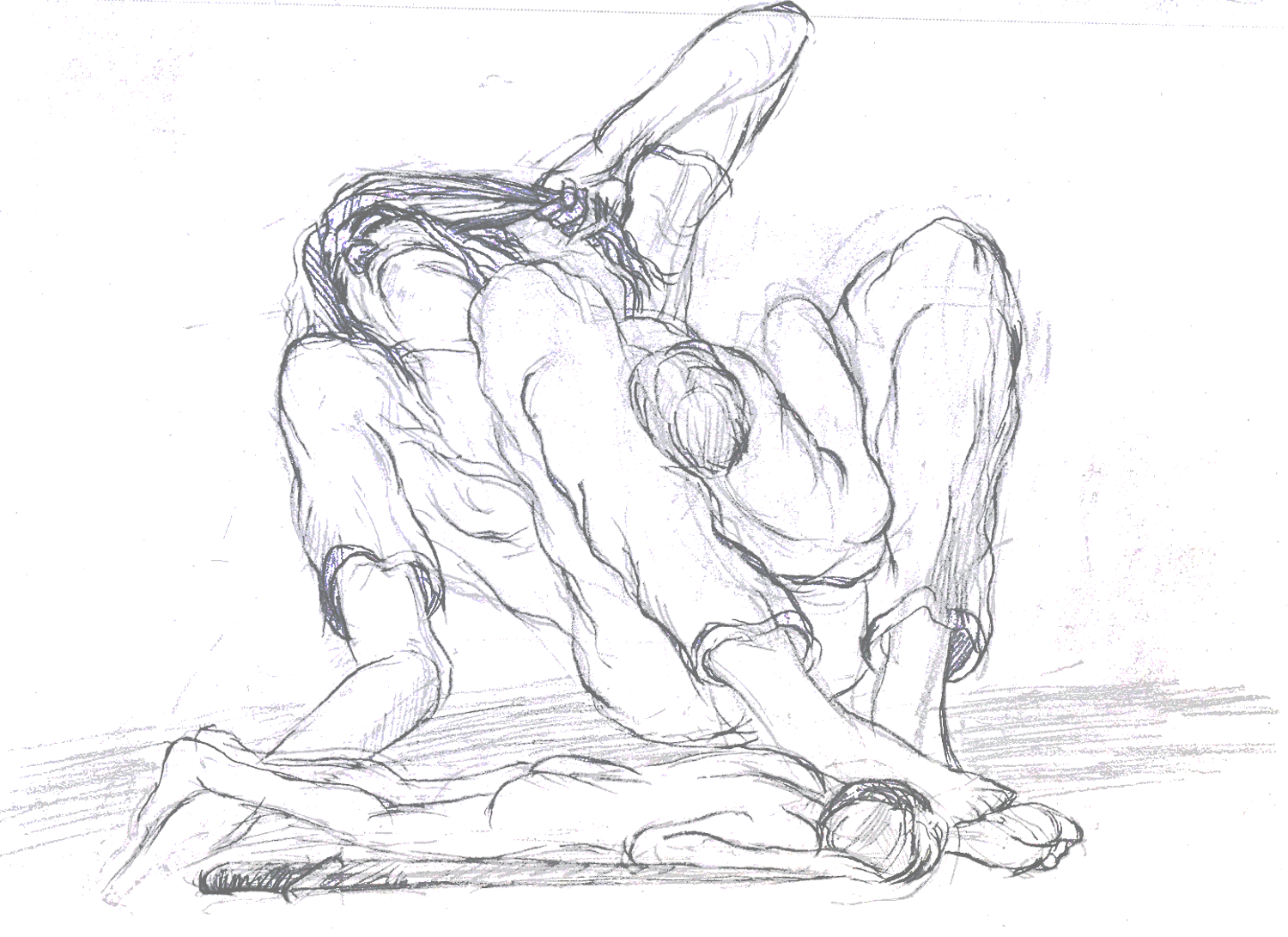

More Information - artwork "Medea" by Kevin Tuttle

- original program booklet in German

- English Translation

“Look at me”

Michael Hersch’s MEDEA

by Egbert Hiller

“As she lay wrestling and with all her reason unable to master her madness, she said, ‘Medea, you struggle in vain.’” The ancient poet Ovid gives the magical female figure of Greek mythology a great deal of attention in his “Metamorphoses,” and in these words, near the beginning (lines 10 and 11) of his reflections on Medea, her fate already metaphorically looms: the inescapability of murderous entanglements in the tension between divine providence and her own will, driven first by love, then by hatred and despair. Her husband Jason left her for another woman, years after she helped him achieve power and fame through magic, and in revenge for her spurned love, Medea killed their children. Against the backdrop of this dramatic story and the archaic force of its actions, it is not surprising that the saga of Medea has consistently endured as an important subject in cultural and musical history – up to the present day in the work of American composer Michael Hersch, who delivers the latest sound adaptation with his large-scale “MEDEA” for the soprano Sarah Maria Sun, the Schola Heidelberg, and the Ensemble Musikfabrik.

Hersch is not beholden to the prominent templates, as the harsh cluster-like chords sounding triple forte from the two pianos in the work’s second measure immediately demonstrate. They unmistakably signal that in this “MEDEA,” a monodrama in one act with a libretto by Stephanie Fleischmann, the depths of psychological and emotional extremes will be powerfully negotiated. With increasing emphasis, Medea ponders her own deeds in a harrowing monologue—flanked by a chorus that grows from a commentator and reflector to her alter ego and increasingly identifies itself with her. Almost like a defendant giving a closing argument, as a figure just as self-confident as she is traumatized, she turns to her supposed judge, the audience, but also to imaginary higher authorities and, last but not least, to herself: “Look at me / I am different, strange / You do not know me / The hole in the sky / that always follows me / wherever I fly. / The swaying ground beneath me / covered in the dust / skin and bones / of many generations.”

In these opening lines, Medea stylizes herself as a mysterious “stranger” and plays with the dichotomy between fear and fascination that is still relevant for the perception of the “foreigner” and the unknown. This aspect already comes into play in Luigi Cherubinis’s Opera “Médée” (1797/1802), in which she as a terrifying sorceress celebrates her horrific revenge on Jason. In 1953, the opera gained greater popularity through Maria Callas’s interpretation of the title role. Maria Callas also endowed the figure of Medea with maximum intensity in Pier Paolo Pasolinis’s similarly titled 1969 film, which explicitly highlights the motif of foreignness and her position as social outsider.

“Burden of a fractured past”

A special Medea in every respect is embodied by the soprano Sarah Maria Sun, with whom Michael Hersch collaborates for the first time, along with the Ensemble Musikfabrik and the Schola Heidelberg. As Hersch emphasizes, “The music is specifically composed for Sarah Maria Sun’s almost limitless vocal capabilities. She is both a remarkable musician and one of the most compelling performers of today, and her part is written with these attributes in mind. For me, her voice is inextricably linked to her powerful stage presence and acting skills, and this is reflected in the conception of the work.” So it made sense to also include scenic or semi-scenic artistic elements which, as abstract ideas, spur musical inspiration or concretely are implemented in a musical theater way. Both are the case, because Hersch planned “MEDEA” as a “work of music theater” that can “be presented staged or unstaged.” Today the concert version will be premiered, but it nevertheless lacks nothing compared to a staged version, since, according to Hersch, “Text and musical elements essentially do not require an openly visual realization. Stephanie Fleischmann and I have attempted to convey the complex layers of the piece through music and text in such a way that they appear equally clear or opaque, regardless of the staging scenario.”

Whether staged or not, the core of the material for Michael Hersch lies in the fascination with the mythical Medea, who he projects as an archetype onto the present and in whose mental and emotional afflictions he immerses himself. And the libretto is no preconceived text set to music in the traditional sense, but was instead created in close cooperation with the composer. Text and music form an inner unity. “I know Stephanie Fleischmann from previous joint projects,” says Michael Hersch. “We share certain sensibilities, with a tendency toward severity. We formed the world of our ‘MEDEA’ predominantly from the writings of Seneca and Euripides, but also from Christa Wolf, and above all, from our reactions to them. There is a constant overlap between retrospect and impending crisis. The horror of the story also provides for a kind of structural disequilibrium, which lends itself well both for the integration of the text into the music as well as the decoupling of the music from the text, sometimes occurring simultaneously.”

Stephanie Fleischmann noted that from her perspective, “the text is a meditation on the events that manifested the myth of Medea, as well as an exploration of the consequences of her actions that reverberate into the future. A look back, in order to conceive of moving forward. A reflection on what it means to be haunted by, indeed, imprisoned by the burden of a despicable, broken past, an investigation of the confrontation of the self, the individual, and the community, of remorse and the impossibility of undoing the unthinkable.”

“Stratification of Brutalities”

Medea is representative of the human condition itself, including all its facets from a devoted and unconditional altruism to extreme cruelty and vileness. Myths and stories from all cultures bear witness to this polarity, which, and how could it be otherwise, is also reflected in the arts. One of the most apt characterizations of man with regard to his (self-) destructive energies was formulated by Georg Büchner in his fragmentary drama “Woyzeck” (which Alban Berg transformed into his opera “Wozzeck”): “Every man is an abyss, it makes you dizzy when you look down.”

In their “MEDEA,” Michael Hersch and Stephanie Fleischmann not only draw attention to Medea's deeds , but focus also on the psychological preconditions and fates that lead to them in the first place—which is manifested in her in an exemplary way. “I have always been deeply interested,” explained Hersch, “in human beings who find themselves in threatening situations, whether external or internal, and how they react –individually and/or collectively—to these situations. The story of Medea is one in which threat and its consequences are present from all directions and in almost every dimension. A large part of my work over the past several decades has concentrated on the threats and consequences from within, for example in the form of illness. However, in recent years, I have shifted increasingly to themes in which threats and consequences of violence from without play an important role.”

The outside and the inside cannot (always) be separated from one another, because both spheres are closely interwoven, since external events cause internal reactions, and inner fears and afflictions lead to consequences in the perception of the outside world and the way we handle it. Hersch took this phenomenon into account in the tonal-musical disposition of “MEDEA,” whereby the full-length work is formed in the context of a long creative process: “The musical framework for ‘MEDEA’ changed multiple times in the course of the composition. I originally thought of a piece for voice and ensemble, but the more closely acquainted I became with the material, the clearer it became to me that the soundscape needed to expand and push out onto larger canvasses.

Stephanie Fleischmann and I decided to conceive of the vocal ensemble as a manifold character that contains the array of figures in Medea’s life, as well as the tangle of shattered elements in her own nature. It was a challenge to find a way to capture this stratification of brutalities, both subtle and overt.” On a more intuitive level, the music is close to the words set to music and thus to Medea herself, in that Hersch “reads” the text between the lines and transforms its associative spaces into sound. In turn, the music has a life of its own with its harsh expressiveness, precise dynamic contrasts, and roiling melodic curves. "MEDEA" begins with an extended instrumental overture, in which the catastrophe is not only foreshadowed, but in the performance is already present and experienced. It is brought to bear by instrumental means before the words enter.

“An attempt to not look away”

The aforementioned cluster-like, extremely dissonant chords in measure 2 (see above) have an essential function, marking a kind of initial spark for the subsequent musical progression. It is no coincidence that they reappear shortly before Medea’s vocal entry, since they not only constitute culmination points at key places in the score, but are also the nucleus of horizontal lines, entanglements, and vibrations in their vertical material identity. Through the foil of these piercingly flashing and then held chords, the use of voice appears decidedly tentative and cautious: with the recitation of the first words (“look at me”) on one note (D), the note on the following “I” is raised a quarter tone, whereby the microtonality becomes a gentle expression of strangeness and alienation.

“MEDEA” places high demands not only on the solo voice, but also on the choir and ensemble, and it was precisely the knowledge of their capabilities that gave Michael Hersch the impulse to fully exploit his sound visions: “Writing for these musicians allows me as a composer to push my imagination to its limits, because I know that every sound, every gesture, every mode of musical communication will be explored with absolute commitment and conscientiousness. In many respects, I feel like I have been preparing myself internally for writing this work for many years.”

A significant part in the work's structure is played by Stephanie Fleischmann, whose libretto forms the framework that on the one hand captures the music and on the other motivates it as a moment of counter-tension to the tonal dissociation from the word. “Look at me” are the first and “towards the sun” the last words in the libretto, which sketches an arc of suspense that outlines Medea’s vacillation between self-knowledge and purification, justification and repression, rebellion and traumatic resignation. “Medea was,” says Stephanie Fleischmann, “the granddaughter of Helios, the sun god. In both Euripides and Seneca, she flees the scene of the crime in a chariot that traverses the sky. In Euripides, she says, in two short sentences, that she is sorry for what she has done. But how does she carry the burden of her horrific crime from that moment? It is her flight toward the sun, her embrace of the part-god in her, breaking free from the laws of gravity that weigh on us humans, and leaving the bodies of her children behind that will follow her to the end of time. Could she ever be absolved? We ask that the chorus, that Medea herself, and also the audience, not look away from what has happened. This work is an attempt to not look away.”

Translation from the German into English by Andrew Santora, edited by Dr. Rita Krueger